The Land Development Code (LDC) is Title 25 in the Austin City Code, and it covers the following broad topics:

- General requirements and procedures

- Zoning, subdivision, and site plan rules

- Transportation

- Drainage, environment, water and wastewater

- Sign regulations

- Building, demolition, and relocation permits; special requirements for historic structures

- Technical codes; and

- Airport hazard and compatible land use regulations.

There are many issues to be considered as Austin rewrites its LDC. This article — one of several that CNU-CTX aims to produce to inform the LDC conversation — will focus on just a few:

- Increased density vs. sprawl

- Housing affordability and family-friendly housing

- Live music and art

- Water conservation and quality

Increased Density vs. Sprawl

Population in Travis County is projected to grow at a slower pace now and in coming years than in the late 20th century, owing to saturation within the county and declining birth rates. Figure 1 shows three projections based on demographic assumptions made by the Texas State Data Center (TSDC) at Texas A&M, housing the office of the State Demographer. The TSDC suggests using the 0.5 scenario as most likely; this scenario assumes that the in-migration rate for the future will be one half (0.5) the levels observed in the decade from 2000 to 2010.

The implication of this graph is that within Travis County, population density will increase. The experience of the author as a planning commissioner for 16 years in Austin (1994-1999, 2001-2012) is that many residents – in particular home-owners in detached single-family houses – dislike increases in population density near their homes.

This is a problematic sentiment if widespread enough, as it implies that remote green-field development is preferred. Such development requires new infrastructure that is generally more expensive than increasing infrastructure within the developed city (Chan and Partners Engineering; Smart Growth America). Furthermore, data compiled on a neighborhood-by-neighborhood basis in Austin show that there are wide differences in persons per acre and households per acre by neighborhood, and many residents have excellent quality of life in

higher density areas (Austin Chamber of Commerce; City Demographer).

Figure 1 Projected population growth Travis County using 3 migration scenarios (TX State Data Center

2013)

There are several effects associated with increasing population density and with increasing the mix of land use types in an area. In a lower density residential area, costs per capita of providing infrastructure go up, as mentioned above for green-fields. With increases in residential density, more efficient use is made of the land, which generally reduces housing costs by dividing the cost of the land among more residencies. Multi-family housing uses less water and electricity per capita than single-family housing, all else held equal.

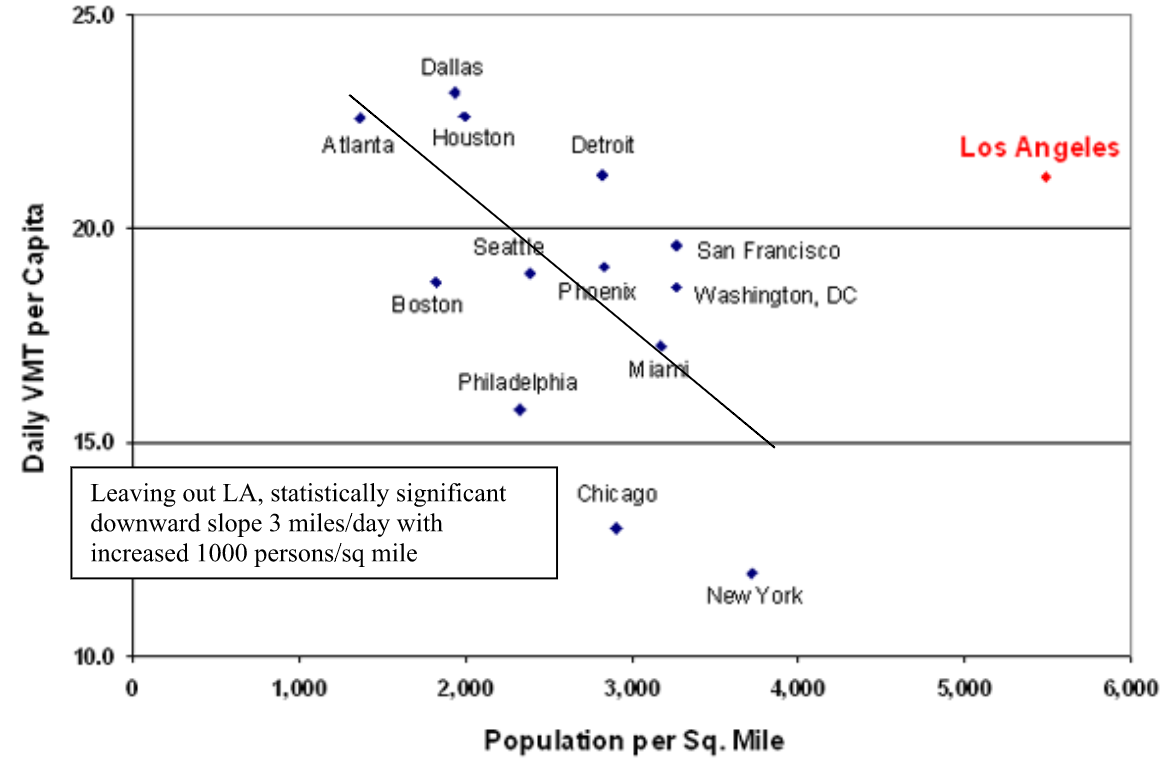

Research shows that in low density residential areas the vehicle miles traveled (VMT) per capita goes up (Figure 2), leading to higher emissions from motor vehicles, increased fuel consumption, and more wear on vehicles. From two households/acre (hh/ac) and up, each observed doubling of residential density reduces driving 25 to 30 percent; and from ten hh/ac and up, each doubling reduces driving 40 percent. (Holtzclaw 1994, 2000). This reduction in driving comes not just from more households per acre, but also the increase in nearby workplaces, retail, services, etc. that accompany residences. These numeric estimates must be viewed with caution, because other factors such as land use mixes, fuel prices, transit availability, and personal preferences all play roles, and there may be significant overall measurement uncertainty.

Several critics of urban sprawl point to compromised public health from lack of exercise related to low-density development (“Does the Built Environment Influence Physical Activity? Examining the Evidence” TRB Special Report 282). Despite the many advantages of higher residential density and increased mix of land uses, many Americans prefer detached single family homes remote from typical destinations. This is not necessarily unreasonable, as many persons prefer the privacy associated with more space per household. I believe it is the role of urbanists to point out the costs and benefits associated with location choices.

Figure 2 Reducing Traffic Congestion and Improving Travel Options in LA, Paul Sorensen 2010;

There are several approaches that could be applied to gracefully increase the residential density and mix of uses so that the community would become more family friendly (e.g., more walkable, safer, less expensive, etc.). Consider the following ideas:

- Along core transit corridors, add vertical mixed-use buildings.

- Allow increased development with “transit oriented districts” at transit stations.

- Redevelop low-intensity non-residential areas with higher residential density; e.g., Mueller, Domain.

- Encourage residential projects at recognized activity centers; e.g., Downtown and UT West Campus.

- Support some close-in green-field intense development; e.g., Robinson Ranch, Goodnight Ranch.

- Provide a modest amount of increased single family & small-scale multifamily in residential areas; e.g., alley flats.

- Allow smaller single family lot sizes (current minimum is 3600 square feet).

These, and other ideas, will be studied in developing the new LDC.

Housing affordability and family friendly housing

Among the many changes in Austin over time are the facts that nearly all demographic groups have fewer children per household than a generation ago, and the cost of inner city housing has gone up as the demand to live centrally has risen faster than supply. It is actually the case that the number of residences in the inner city has gone up, while the count of persons has gone down, and the number of person under 18 years old has gone down more.

This has led to a crisis for the Austin Independent School District (AISD), which studied the possibility of closing several inner city elementary and middle schools in 2011. Several changes to the LDC could help slow or reverse this trend and bring more families with children to the inner city. These include the following:

- Require elevators in multi-family and condo projects, to facilitate vertical travel for parents with small children, kids with bikes, folks needing walkers or wheelchairs.

- Provide first floor space in multi-family buildings for bikes and strollers.

- Provide builders incentives for playgrounds on large multi-family developments.

- Set standards for sharing City resources such as parks and libraries with AISD to make schools more attractive to families.

- Require that any redevelopment of properties that would require relocation of residents to restrict evictions to the period outside of the regular school year.

- Require that any redevelopment of properties that would require relocation of low income residents be accompanied by relocation assistance that would help residents find new housing nearby.

Both of these last two points are prompted by research at The University of Texas at Austin that looked at the relationship between household income and the frequency with which kids change schools (“mobility”). See Figure 3. A finding was that mobility was both related to higher levels of poverty in the school, and with lower student achievement. The point is that all else held equal, if a child is not bumped from school to school as parents move, the better the child is likely to do in school achievement. Thus, more stable family housing in the inner city could help improve outcomes for more students.

Figure 3 Mobility and poverty rates in high & low poverty AISD high schools,

http://www.ci.austin.tx.us/housing/downloads/Jennifer Holme.pdf

Adding new requirements generally also adds increased costs for construction and ongoing operations and maintenance. Overall, an effort will be made to simplify the LDC so that permitting is easier, reducing initial costs for construction. Examples of simplified permitting include limited use of form-based codes that specify more design up front and but allow greater flexibility in the location-specific range of permitted land uses.

Already there are indications that some single-family home owners have concerns about reduced certainty in what types of multifamily, office, or retail uses will go on specific tracts near their homes. A balance will have to be struck in terms of what requirements will exist under form-based code and how housing affordability can be boosted by using form-based code.

Other forms of relaxed permitting could apply to secondary units. Currently rules allow secondary units such as a garage apartment or alley flat if 1) a lot exceeds 7,000 square feet in SF-3 or more intense residential zoning; or 2) if allowed on standard 5,750 square feet lots in SF zoning under a neighborhood plan. A secondary unit can be added with an increase from 45 to 55 percent impervious cover in some cases if the second unit is priced to meet some affordability price point. Small lot single family (SF4-A zoning on a 3,600 square feet lot) allows 55 percent impervious cover.

Perhaps all SF-2 and SF-3 residential zoning outside of flood-prone areas could have a 45 percent impervious cover for one residence, but 55 percent or higher impervious cover if there is a second unit. Some argue that relaxing regulations would drive up the value of the land causing higher taxes. By granting an entitlement city-wide rather than restricting such an entitlement to a few neighborhoods, the relative advantage to developers when market values of property increase owing to relaxed standards would be diluted, thus not causing any tax bill increase.

Art, Music, Culture

Austin enjoys a world-wide reputation as an arts and entertainment center. While this is obviously a draw for tourism and a boost to local quality of life, there is evidence that creativity in many forms is at the heart of Austin’s success as a city. One important piece of evidence was the publication of Richard Florida’s Rise of the Creative Class (2004), which helped to describe Austin’s success over the late 20th century: that a tolerant community attracted and bred talented residents who in turn attracted investment in technology industries. Florida placed Austin, along with San Francisco, as the most creative cities in the U.S.

Concerned that nothing lasts forever, many citizens have worked over recent years to sustain our arts culture. In response to concerns that the relatively rapid rate of change in Austin could negatively affect our artistic and economic creative culture, the 2008 CreateAustin Cultural Master Plan was put together as the result of a two-year process of cultural assessment, research, and community engagement undertaken to chart a course for Austin’s cultural development over the next 10 years.

CreateAustin concluded: “In order to sustain the unique qualities that make Austin special, attention is needed to support the infrastructure that can sustain Austin’s culture of creativity.” The most important features of CreateAustin have been integrated into the Imagine Austin Comprehensive Plan, and a non-profit organization, the Austin Creative Alliance, has been active at tracking the slow progress of implementing these two plans.

One important aspect of the creative community in Austin is the live music industry. In its biennial survey of the Austin music industry in 2013, Austin Music People (AMP) reported that the industry serves as an economic driver for our community, generating more than $1.6 billion annually. AMP is a nonprofit founded to follow-up on recommendations from the City’s 2008 Live Music Task Force. That Task Force had found that earnings for musicians over past 20 years had remained flat and that musicians suffered a high rate poverty and problems with health care and insurance.

The Task Force had also found that there was increasing pressure on music venues owing to rising land value leading to displacement and concerns over noise affecting nearby residences. One example of these pressures is the Red River Music District, which was cited in the 2011 Downtown Austin Plan for special designation as an official Live Music District. Much of the proposed district lies within the Waller Creek district deliberately slated for new development as its flood plain is reduced by the Waller Tunnel flood control project. One example of the concerns over noise is the dynamically evolving Rainey Street District, where the City has already lowered the property-line sound limit for bars with live music.

Overall, there is a need to pay attention to “cultural arts” in the LDC – e.g., how to help provide performance and rehearsal space? Where to add public art? How to include arts venues in new developments? How to sustain music districts in the face of pressure?

Water Conservation and Quality

Many Austin area residents are concerned that water will be a limiting factor in constraining the area’s growth. However, there are areas with substantially less rainfall than Austin’s 34 inches annually, such as Phoenix (8.2 inches) and Las Vegas (4.2 inches), which are likewise fast growing metropolitan regions.

Nevertheless, droughts and possible long-term changes in rainfall require longrange planning to prevent water shortages or run-away cost increases. The Austin Water Utility and the Imagine Austin Comprehensive Plan have detailed steps to reduce per capita use to 140 gallons per day. The LDC could include new ideas such as limited gray-water irrigation rules and onsite rainwater

capture rules. More multifamily and small-lot single family units with smaller lawns, or well planned traditional single family developments using xeriscaping or drought-tolerant landscaping, can reduce water use and could be encouraged in the LDC. The LDC may consider new conservation tools in public infrastructure, such as “green streets”, in which rain water is captured and detained to water street trees, or rain water capture incentives for private commercial developers or requirements for municipal buildings, etc.

Looking ForwarD

The LDC rewrite project will draw on the knowledge and skills of the City staff, the consultant team led by Opticos Design, an 11-member Advisory Group, and the broader Austin community. In addition to concerned residents and expert stakeholders in civic and commercial special interest groups, a key resource to draw upon will be the Community and Regional Planning Program of the UT School of Architecture.

Significant contributions from this group to guiding Austin’s future can be found at the UT SOA website. These include studies on the following topics:

- Alley Flat Initiative

- Corridor Planning

- SMART Code

- Retrofitting suburbs

Much work remains. Just some other controversial questions are:

- Do we have rules that would fail a cost/benefit test based on observed trends? (e.g., McMansion, short-term rentals, commercial design standards, compatibility standards, heritage trees, etc.)

- Would new rules that are stricter in some areas and relaxations in others help? (e.g., increased rainwater capture, relaxed parking requirements, etc.)

- Would more emphasis on “form” and less on “use” offer better zoning approaches in some redeveloping areas?

Over the next 3 years, watch for notices about Community Forums, Speakers Bureau recruitment, LDC Advisory Group meetings, Planning Commission meetings, online surveys and paper balloting, etc.